The Secret Life Of Your Clothes

BBC2

“The strange journey of Britain’s cast-offs is the subject of an

arresting BBC documentary” – Daily Telegraph

Reviews

Like many families across Britain, we have a box of clothes sitting by the front door almost permanently, ready to be sent to the local charity shop. But, once we’ve lugged them down the road, I always feel slightly offended on my daily walk past the shop, because my rather natty cast-offs never seem to make it into the window display.

Now I’ve discovered how unlikely it is that any of the shirts, suits, children’s T-shirts and jeans I donate actually end up being sold in that particular branch – or indeed in any of the charity’s outlets. They are, it turns out, just as likely to be sold on the side of the road in the tiny village of Gyen Gyen in Ghana as on the racks of Marie Curie in Islington.

The strange journey of Britain’s cast-offs is the subject of an arresting BBC documentary. It traces how the rise and rise of fast fashion in Britain has helped fuel a multi-billion pound second-hand clothing industry in Africa, providing countless people with a livelihood, but also – worryingly – damaging local textile manufacturers in these developing nations.

Figures vary, but one study suggests as many as eight in 10 garments are not actually sold in charity shops. Even the Charity Retail Association estimates that 41 per cent are sold on to commercial recyclers, and 4 per cent go to landfill.

Britain is, quite simply, addicted to cheap fashion. Consumers buy an estimated £1,700 of new clothes every year, according to one government agency, and women have four times as many clothes in their wardrobe as they did back in 1980. This means we have more to give away than ever before: more than 350,000 tons were donated to charity shops last year.

But when it comes to buying them back, we’re not interested. Many consumers would prefer to go to Primark, Topshop or George at Asda to buy a new pair of £6 skinny jeans than pick up an unfashionable pair for £5 from a charity shop.

Paul Robinson, featured in the programme, is one of some 5,000 textile recyclers, many based in the Midlands. He pays charities about £500 a ton for clothes and then sorts them. Those that are only good for turning into rags are sold to the likes of upholstery suppliers; the rest are exported.

Alan Wheeler, director at the Textile Recycling Association, says people who raise their eyebrows at money being made from donated clothes are being naive. His industry, he explains, is a vital cog in the life-cycle of clothes, saving them from going into landfill and passing on as much as £100 million in turnover to the charities.

The biggest buyer of these cast-off clothes is Ghana. Every year, 30,000 tons of used clothing arrives on the docks of the capital, Accra. It comes in huge bales, weighing between 45-55kg, and the majority of it is from Britain. There, our unwanted Manchester United football shorts and Next chinos help fuel a booming industry. Locals even have a name for the garments – obroni wawu – which means “dead white man’s clothes”.

Eric Forson is one of the many wholesalers based in Accra. He sorts his purchases into different tiers (a newish M&S Blue Harbour or TM Lewin shirt is grade one, while frayed items are grade three), before selling them to merchants and shops around the country. Many are sold on the roadside in remote villages, where a single item costs around 25p.

Wearing Calvin Klein trousers and an M&S shirt, Forson explains the appeal of our cast-offs. “It depends on what the person wants to buy,” he says. “But obroni wawu goes faster, because it is a little bit cheaper for the masses to afford. If you have 50 Ghanaian cedi [about £9] in your pocket, you can go to the market and buy a lot of shirts. But when you go to the shop, you buy only one or two. I prefer to go to the market and buy the used ones.”

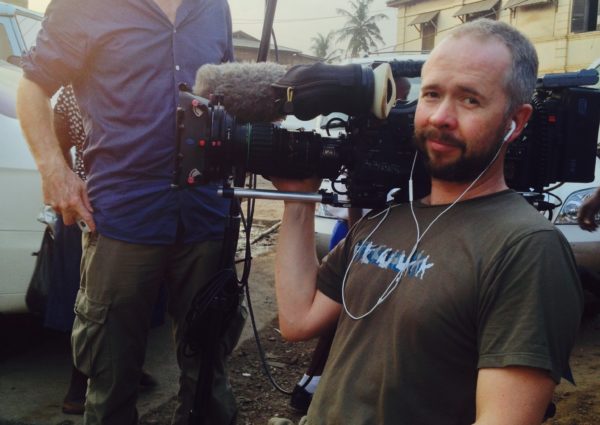

Ade Adepitan, the Paralympic basketball player who presents the documentary, says this is the “last place” he’d expect his donated clothes to end up.

“What’s more surprising is these people have next to nothing, yet they’re probably supporting a lot of UK charities,” he says. “And what’s even weirder than that, is those charities are probably giving money to Africa to support these people, so it’s just a bizarre money-go-round.”

Africa, particularly west Africa, has been buying Western cast-offs since trade was liberalised in the Eighties. Used clothes represent more than half of the clothing market in most sub-Saharan countries, with 81 per cent of clothes in Uganda, for instance, being second-hand.

And it’s not just because they are cheaper. Many of the younger consumers in these countries actively prefer to buy Western fashions, even if they have been worn. Dr Andrew Brooks, a lecturer in development studies at King’s College London, reports that it is quite common in Mozambique for local salesmen to scuff newly made Chinese shoes and conceal them among used shoes from Europe in order to make them more desirable to young shoppers.

It sounds like everyone’s kept happy. But there is growing concern that the appeal and ever lower prices of brands such as Ben Sherman, Fat Face, Jigsaw and Primark are forcing local manufacturers out of business. Not only that, but the rich culture of fabulously intricate textiles that have been produced in Africa for generations is in danger of dying out.

To combat the influx, some African countries, including Nigeria, have banned the import of second-hand clothes from Europe. The Ghanaian government has recently launched an initiative encouraging people to wear traditional, locally manufactured clothes on Fridays.

The number of textile and clothing workers in Ghana fell by 80 per cent between 1975 and 2000. Akosombo Textiles, one of Ghana’s largest manufacturers, was producing nearly 2 million metres a month in 2009, but this has fallen by 75 per cent. “It’s quite an urgent situation; we feel like we’re on the brink of not being able to carry on,” says Steve Dutton, the company manager.

Experts say it is impossible to prove conclusively that our monthly trips to local charity shops are a direct cause of this decline, but they have most likely played a role – not least in encouraging demand for Western fashions.

On the positive side, according to the Kenya Institute of Public Policy Research and Analysis, the used clothing industry supports some 10 million jobs in Kenya. So don’t stop putting cast-offs in the box by the front door just yet.

Our Superdry T-shirts and Dorothy Perkins skirts go on a highly complex voyage when we give them away. Not just geographically – from a factory in the Far East to a British high street to our homes and finally to a Ghanaian village – but an ethical one, too. More than enough to give you pause for thought next time you pass that window display.

The complex patterns of bright colours adorning gowns made of traditional kente cloth have long been the de riguer tribal statement in Ghana. Now there are fears they are facing extinction due to a British invasion in West African fashion, as they are replaced by the “Obroni Wawu” – the dress of the dead white man.

Fashion cast-offs from UK charity shops are said to be killing traditional garment manufacture in Ghana. The £50m-a-year second-hand clothing trade in the West African nation, much of which is dependent on unsold garments from British charity outlets, has led to the country becoming a “dumping ground”, according to Ghanaian cultural experts and clothing industry bosses.

The impact of the Obroni Wawu has even led some companies to introduce “thank Ghana it’s Friday” days, when employees are asked to wear African dress to work.

The extent of the cultural problems caused by British clothes swamping the market is revealed in a BBC Two documentary to be shown on Monday night.

The Secret Life of Your Clothes found fashion castoffs from British brands such as Superdry, Next, Dorothy Perkins, Primark and Ben Sherman being bartered for a few pence in remote villages in rural Ghana.

Wholesalers distribute vast quantities of clothing bundles – imported from Britain after being collected from a wide range of charity outlets including the Salvation Army, the RSPCA and Mind.

Fashion cast-offs are said to be killing traditional garment manufacture in Ghana “The [charity] bundles from the UK were seen like gold dust,” said the BBC2 documentary’s presenter Ade Adepitan. “These clothes are often made by the poorest people in the world for big British companies. We wear them for a month or so and give them to charity shops who sell them back to these poor people, who are funding the charities in the UK.”

Eric Forson, an Obroni Wawu wholesaler based in Ghana’s capital Accra, tells the programme: “We used to get [clothing] from Manchester, sometime we go to Leeds, sometimes we go to Coventry… In terms of second-hand clothing, the UK stuff is best.”

Holding up a Ben Sherman shirt sold on by a British charity shop, Accra trader Asiedu Aboaden explained that UK clothes are preferred to those from the US because of “the smaller sizes”.

In Kumasi, capital of the inland Ashanti region, bales of British charity clothing swap hands for £40. The least-wanted garments are carried by small traders to rural villages, such as those close to Lake Volta, where they are sold for a few pence but are still in great demand.

Osei-Bonsu Safo-Kantanka, a historian, said the trade in Obroni Wawu was having a negative impact on demand for clothes made from the traditional Ghanaian kente cloth, which is crafted by hand on looms. “One has to undergo training, a year or more, to learn how to weave the very simple kente,” he said. “Economics come to play… Second-hand clothing brought in from Europe and America is cheaper, far cheaper.

“We were trained, even when I was young, to believe that everything West is civilisation. Our belief and respect for our own things has faded to a degree that if we are not very careful sometime, somewhere, someday… we would not see some of our own things anymore.”

Steve Dutton, an ex-pat Mancunian who runs Akosombo Textiles, one of Ghana’s last remaining cloth factories, said that the industry was already under grave pressure from fake African prints produced in the Far East. Some even come with fraudulent Akosombo labels. “It’s difficult for me to overemphasise just how close we are to closing down. I’m very, very worried that this copying is going to destroy us.”

But Adepitan said he did not feel British charities were at fault for their role in the Obroni Wawu trade. “You cannot blame the charities – they are getting clothes in such vast quantities they cannot sell them all.”

‘I’m wearing a shirt by Marks and Spencer and a pair of Calvin Klein jeans,’ beams Eric Foreson, a trader from Ghana’s capital, Accra. ‘It happens like that sometimes.’ But Mr Foreson’s designer threads didn’t come from a boutique. Instead they arrived in a batch of second-hand clothes sourced from a British charity shop.

Rather than being donated to the world’s poorest people, as a new BBC documentary makes clear, cast-off clothing has become a multimillion pound business – and the poor are paying.

The UK spends £60bn a year on new clothes and much of what is discarded ends up in high street charity shops.

Clothes that aren’t sold to shoppers go to recycling plants and from there, to Africa. Although the majority of African countries import cast-off clothing, Ghana gets the most with 30,000 tonnes arriving in capital Accra each year.

Locally, it’s known as ‘oboni wawu’ or ‘dead white man clothing.’ ‘Oboni Wawu goes fast because it’s a little bit cheaper for the masses to afford,’ explains Foreson, who owns one of the biggest wholesale businesses in Accra.

‘If you have 50 Ghana Cedi (approximately £8), you can go to the market and buy a lot of shirts,’ he explains.

‘If you go to the shop, you buy only one or two shirts. People prefer to go to the market and buy the used ones.’

Much of what they do buy comes from the UK. ‘We used to get from Manchester,’ adds Mr Foreson.

‘Now we go to Leeds. We go to Coventry. This,’ he says, gesturing at a bale of clothes, ‘is from Birmingham. In terms of second hand clothing, UK stuff is the best. Many people import it more than the other stuff.’

According to Ase Adu, the owner of a boutique selling upmarket second hand clothes to Accra’s elite, the reason for buying British comes down to two things: size and quality.

‘We prefer the smaller sizes,’ he explains. ‘That’s why we prefer the UK over the US clothes. People like the quality.

‘You can get Paul Boateng, Next, River Island Marks and Spencer, Ben Sherman. So many, many, things.

Clothing is graded with buyers like Adu taking the best pieces, while second and third grade clothes are sold on – the tattiest ending up in the hands of the very poorest who buy them for as little as 25p.

But while Ghana’s second hand clothing boom is making some people rich, for indigenous textile producers, it has been nothing short of disastrous.

‘In 2009, we were producing two million metres of cloth a month, and over that period, it’s gone down by 75 per cent,’ explains Steve Dutton, the Manchester-born overseer at the Akasombo Textiles factory near Lake Volta, which employs 2000 people.

‘It’s quite an urgent situation and we’re on the brink of saying, we can’t go on.’

And it’s not just local textile producers that are suffering. ‘Second hand clothing brought in from the UK and America is cheaper, far cheaper,’ adds Ode Bonsu, a local historian.

‘We were trained, even when I was young, to believe that everything western was civilised. Our belief and respect for our own things has faded to the point where if we are not very careful, some day somewhere, we will not see our own things any more.

‘These days, everybody is keeping an English name in addition to his own name. And they prefer being called their western name to their own name.

‘That alone should tell you. The food that we eat has changed. We now eat western food as much as our own food. It is killing our culture.’

Not that the traders making a killing off the back of British charitable donations care. ‘It’s a big and very lucrative business,’ says one.

‘You can make money every day. On a good day, you can make, lets say, 100,000 Ghana cedis (£25,000). I’m telling you, this business is very lucrative business.’

Recycled to Africa The Secret Life Of Your Clothes (BBC2, 9pm) Ade Adepitan follows what happens to second-hand British garments in a This World film that takes him to Ghana. Known as “oburoni wawu” (a white man has died), western countries’ cast-off clothes are a multi-million-pound industry, providing jobs in dyeing, ironing, altering and transporting them, as well as trading them at market. Adepitan meets people in the chain, but his film also reflects the impact cheap Marks & Spencer or Next shirts has on Ghana’s fashion and textile companies, which cannot compete on price and may not survive as demand for African clothes dwindles.

Leaflets and bin liners are for ever being put through letterboxes with the request that people donate their old clothes to those in need. Every year Britons respond by giving away thousands of tonnes of items, most of which unfortunately never see the inside of a charity shop. They are shipped to Africa to be bought by the world’s poorest as part of a multimillion pound industry for the benefit of wholesalers, market traders and — above all — the importers. To make matters worse, local textile industries are being destroyed by this flood of Western clothing. Presenter Ade Adepitan travels to remote villages in Ghana where everyone is dressed in secondhand garments from Marks & Spencer, Next and Dorothy Perkins.

The majority of donations to UK charity shops don’t actually end up on the rails: instead they go to African marketplaces, fought over by those intending to sell them on. Now Dorothy Perkins et al have largely replaced traditional African dress, even in the tiniest of villages. Here, Ade Adepitan visits Ghana, where he discovers how this influx of high-street garb – known as “obroni wawu” (roughly equating to “dead white man’s clothes”) – is undermining the local textile industry.

Ade Adepitan presents this eye-opening film that reveals what happens to the unwanted clothes we give to charity shops. It turns out that most are exported to Africa, so he heads to Ghana to meet the people making a handsome living from our cast-offs and assesses the impact the trade is having on Ghanaian culture.