Louis Theroux: Ultra Zionists

BBC2

“Louis Theroux visiting the West Bank almost sounds like a joke. But shelve

any scepticism as this works superbly.” – Radio Times

Reviews

Louis Theroux visiting the West Bank almost sounds like a joke. But shelve any scepticism as this works superbly.

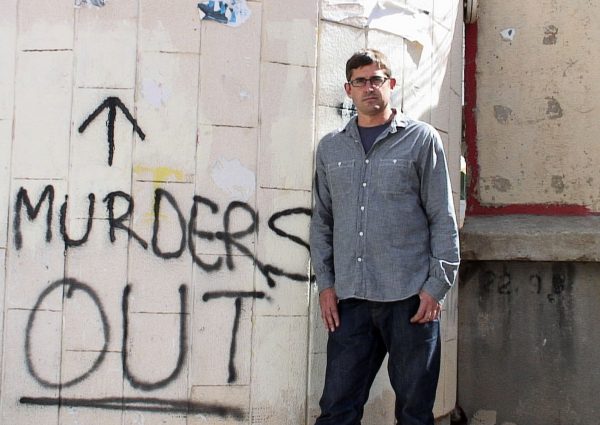

Meeting extremist Jewish settlers in areas that are Israeli-occupied but (according to international law) Palestinian by rights, he reveals the bizarre details of life in towns where day-to-day scuffles, stone throwing and name-calling between Arabs and Jews are such a fact of life, they’re almost ritualized into a sinister game.

If that sounds like trivialising the issue, he really doesn’t: Theroux’s observational style reveals more about the intractable human reality than a dozen po-faced news reports.

Louis Theroux, your TV guide to society’s colourful fringes, last night took a tour of the West Bank, the white-hot centre of global human irrationality. In Louis Theroux: Ultra Zionists (BBC2) he met Daniel, a hardline nationalist Israeli from Australia whose special gift, it seems, is remaining oblivious to things that do not underpin his worldview. He works for an organisation that houses Jews in the overwhelmingly Palestinian East Jerusalem, Israel’s annexation of which is recognised by no other country. “So what for the world?” said Daniel. “It doesn’t bother me.” Theroux accused him of talking as if the land meant nothing to Arabs. “Well, it doesn’t,” said Daniel. “This is the Jewish homeland, and there’s never been a Palestinian people. If they want to express themselves nationally, they can express themselves somewhere else.”

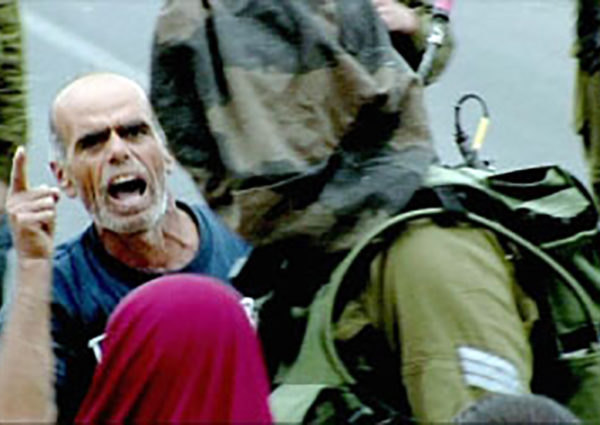

Daniel believes the enmity between Jews and Arabs is biblically decreed, which probably explains why he thinks it’s OK to say things like that. It makes him, if nothing else, a pretty unpleasant neighbour. If you stripped away his religious extremism and blinkered nationalism, he would still be a jerk.

Theroux wisely resisted any attempt to make sense of what is known in online circles as the I/P question. Instead he concentrated on individuals, and why they chose to live in an atmosphere “somewhere between embattled and entitled”. In a way it was all about being bad neighbours – almost everyone he interviewed had long since divested themselves of any responsibility for what happens to those on the other side. The young man who lived in an illegal West Bank encampment – illegal in Israel, even – had a vision of a greater Israel that did not stretch to thinking about where the Palestinians, whose land it would include, might go.

The weirdest encounter was with a group of American Christians who had volunteered to pick grapes at a West Bank vineyard. “It’s a labour of love for the nation of Israel,” said one. Like Daniel, they seemed incapable of viewing the situation as in any way complex. In general, when Theroux goes on one of his adventures one is forced to admire his daft, naive courage. In this case I was left admiring his patience.

There are times when one wishes Louis Theroux would stop going to difficult places and go back to meeting difficult celebrities, but his subject is always the same thing: extremity.

In The Ultra Zionists, in which he visited Israeli settlers in the West Bank, he proved again that the only ultra about him is that he is ultra relaxed. This is as well since the formalized rituals of Palestinian v settler disputes he found would drive most of us to rage: Jews buy property in a Palestinian enclave, the locals, resentful, dump rubbish at their door and stone their cars. Armed police or IDF are called. Next thing you know some Palestinian is lying dead and a suicide bomber is on his way to a Jerusalem café.

Theroux cleverly got Daniel Luria, who works for an organization that helps Jews to buy property in East Jerusalem, to agree that he saw the enmity between Arabs and Jews and biblically decreed. So was it possible that he was creating that enmity so as to fulfill the messianic prophecy? Not at all, he replied: “The sons of Esau do not like it that the sons of Jacob have come back here.” Luria was good value: intelligent, civilized and articulate – until it came to his faith, when he became a right old Jacob.

His main competitor in religious nonsense came from American Christians toiling in a Jewish vineyard, presumably so they will have something to drink when the Kingdom of God re-establishes itself on this soil. A student living in a tent decorated by portraits of his favourite rabbis asked Theroux if he liked his atheism. “I like it a lot,” he said. And no wonder.

Louis Theroux might be just what the Middle East needs. In The Ultra Zionists, the gangly investigator took his brand of quiet, schoolboyish questioning to some of the least quiet, schoolboyish people on the planet.

We all know about the West Bank. We hear about it all the time. But we don’t – or at least I certainly didn’t – know very much about what life is actually like there. Conflict-ridden, sure. Hostile, yes. But also profoundly, profoundly weird. As Theroux followed a series of settlers around, we saw just how up close and personal things can get. Defiant in their divine right to what is legally not their land, whole families live day in day out blocking out the taunts, the loathing, the rage of their neighbours. In one town, residents routinely dump their rubbish outside the local settlers’ house. Verbal abuse is constant. Why do they do this? Why not just return to Israel and live peacefully? It’s utterly, utterly baffling.

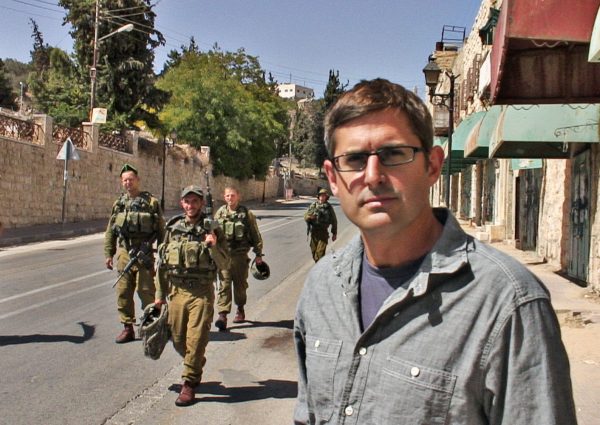

Of course, it helps that the Israeli government provides security for all these people, despite proclaiming their actions illegal. Border police and security escorts surround their homes, throwing tear gas in response to children’s stones and arresting youths they consider agitators. Theroux joined a group of protestors to see how hot things can get. The answer? Very. The soldiers’ accents sound exactly like the South African one. Why is that? I’ve always wondered.

Neither side in the conflict came across particularly well, though it was the bloody single-mindedness of the Zionists that stole the show. Almost all of them said they would stay where they were even if military support were withdrawn. “We’re the only country that accepts a united Jerusalem,” boasted Danny, Theroux’s sometime guide. “The world’s got a problem. Doesn’t bother me.”

After encounters in the ganglands of Johannesburg and crime-ridden Lagos, and with meth addicts in Fresno, California, Louis Theroux continues to visit some of the world’s most violent and dangerous places and ask its people some searching questions. Tonight, he’s meeting ultra-nationalist Jewish settlers in the West Bank.

Many of the area’s 2.5 million Palestinians have found themselves displaced by an influx of 300,000 Jews. The Jews see Jerusalem – and East Jerusalem in particular – as rightfully theirs, promised to them by God, and those that Theroux speaks to show no sympathy for the Arabs who have lived in the area for centuries. Despite their small numbers the settlers are well-protected by the Israeli government and constantly escorted by soldiers as they are routinely attacked by angry Arabs. Theroux meets a number of these Jewish settlers, beginning with Daniel Luria, originally from Australia and a member of the group Ateret Cohanim which aims to return the Jewish people to East Jerusalem by buying up properties in Palestinian areas – something which they are not legally allowed to do. When reminded that many people see the Jewish occupation of East Jerusalem as illegal, Luria responds dismissively: “We’re the only country in the world that accepts United Jerusalem as United Jerusalem. I know that. So what for the world? It doesn’t bother me.”

The G2 interview: ‘I’m not that comfortable doing polemic’: Louis Theroux talks to Decca Aitkenhead

What is it about Louis Theroux that makes people want to show him how odd they are? For more than a decade now, ever since Jimmy Savile confided on camera that he used to beat people up and lock them in a basement during his career as a nightclub manager, Theroux’s subjects have been sharing their strangeness with him. But I’ve never been able to work out why. Critics have accused the presenter of tricking interviewees by pretending to be a bumbling fool – a faux naif – yet within minutes of meeting him, I think I see the real reason why his subjects reveal all. I don’t know him at all, but would quite happily tell him anything.

For a big man – well over 6ft – he is remarkably gentle in his bearing, but it’s his eyes that invite confidence, for he squints with an expression of the most profound compassion and concern. If I didn’t know what he did for a living, I’d guess he was a therapist, because it’s the expression a good shrink would wear while a client recalled some terrible trauma. In his forgiving gaze, it’s impossible to believe that anything you say could ever cause offence or shock – and so, of course, people come out with all sorts, forgetting that viewers may be rather more judgmental than Theroux.

Because he first became famous for making films about somewhat sensational subjects – the sex industry, UFO abductees and the like – there has often been a suspicion that this slightly unworldly character we see on our screens must be a clever comic creation. How could a first-class history graduate from Oxford really be so non-judgmental? His latest film follows ultra Zionist settlers on the West Bank – hardly an unreported story, but one he says he came to with a genuinely open mind. Did he really not have a view about them before embarking on the film?

“Not really, no. I just thought, this is a community of settlers who live quite a suburban life, many of whom are emigre Americans, and it struck me as both very relatable, in terms of the life they lead, and at the same time utterly surreal, in terms of the extremism of their beliefs and the implications of their beliefs for people on the ground.”

And by the end? “Well, based on what I saw, their presence is, to my mind, highly morally questionable. By the end of it I was more shocked. But also, I’m aware,” and he sighs slightly apologetically, “that I don’t feel I line up comfortably with this sort of knee-jerk leftwing critique of – I know that’s very loaded,” he adds quickly, “like I’m not knee-jerk – but for example, I thought a lot about nice Israelis I’d met, and about the dilemmas of being an Israeli, and the unquestionable fact that large portions of the Palestinian community would like to see Israel wiped off the map. So it’s easy to be glib on one side or the other, and I try to resist that.”

In the film he asks a settler if he considers himself equal to Palestinians, and the bald reply – “No” – is all the more arresting in the context of a film that doesn’t automatically vilify the settlers, but instead shows the bizarre and heartbreaking consequences of their conviction of divine entitlement to the land.

Some viewers may wish that Theroux was more aggressively confrontational, but he says mildly, “I’m not that comfortable doing polemic or being strident. It’s not me. I think what I’m good at is getting to know people, and trying to build a relationship over a few weeks and trying to get to the truth.” Did he like the settlers? “I did quite. But my films are about attempting to square the fact that it may be someone you like, but it’s also someone doing something that may be morally questionable. That’s the whole thing – that’s what I do. That’s my job.”

His job has evolved over the years, though, into something very different from Louis Theroux’s Weird Weekends, his first series of documentaries that followed obscure, mostly American subcultures such as porn stars, swingers and survivalists. A series of celebrity documentaries followed, featuring Neil and Christine Hamilton, Max Clifford, Keith Harris and other names from that sub-strata of fame occupied by characters who could most charitably be described as colourful. In recent years, however, his subject matter has become less comical, ranging from lifers in San Quentin jail and gang bosses in Lagos to crystal meth addicts in California and crime fighters in Johannesburg.

At a time when most television journalism is moving in the opposite direction, I wonder why he decided to move away from amusingly wacky celebrities and crazies, towards more meaningful and mature films. “I think there were a few things going on. One was that after the celebrity stories, there’s a sense in which – well it’s just not a very nice way of working, to be honest. It’s quite uncomfortable having your access being subject to the whim of one person, and in a sense that emotional and journalistic contract I had with the subject was quite complicated. It was a warts-and-all contract that depended on prolonged access in which they had no editorial control – but they controlled the access. They were surrendering a lot, so it was difficult to go through that with equanimity and tranquillity.”

What does he mean? “Well, I really do like to be open, I don’t like that feeling of holding back difficult questions. I feel like the more I can be transparent in the way I approach a story, the more it makes a satisfying programme. For example, in the film I made about Nazis, this guy said, ‘I think black people look like monkeys’, and I said, ‘Do you think you’re better looking than Denzil Washington?’. He said, ‘I think I’m a lot better looking.’ I said, ‘I think you’re deluded.’ And it was really satisfying to be able to just say that.”

That’s somewhat ironic, I say, because a common critique of Theroux’s work is that he doesn’t do enough of that. “I know,” he agrees. Does it annoy him? “No, I think they’re just reacting to my earlier work, Weird Weekends, which hinged on me going, ‘Oh look! I’m going to explore this world, it’s going to be great being a porn star!’ It was a very different tone.”

He feels more comfortable now, he says, about challenging his subjects. “I used to be very timid, and I feel as though I’m quite robust now when I talk to people. I never misrepresent my position – you’ve got to be strong enough to make the argument and marshal the case. I don’t know if other people get that, though.” He thinks it might be his politeness that gets mistaken for complicity, and I suspect he may be right, for even off-camera he has a kind of courtesy that can come across as intellectual timidity.

And he has – or at least, used to have – an unusually exaggerated sense of responsibility towards his subjects, so much so that in 2005 he revisited many of them to write a book, The Call of the Weird, examining his relationships with them. “Did they know what kind of programme I was making? Did they think we were going to be friends? That we would keep in touch? But when I went back I realised I cared more about those questions than they did.

I realised that sense of obligation was really in my own head – they didn’t think about it.”

He offers the admission rather ruefully, but it was another one he made when the book was published that I found more surprising, so I quote it to him. “When I spent more time with the people,” he said at the time, “I realised that whatever was originally weird and funny about them turned out to spring from some quality of being damaged that wasn’t funny at all. That was a bit sad. I didn’t notice that the first time around.” Was it really not apparent to him that militia men, say, or porn stars, might be damaged?

“Yeah,” he giggles softly. “I probably should have realised a bit sooner. If I can spin it in a positive way, though, I tend to take people at their own word. I don’t tend to quickly think, oh well you’ve obviously had a nervous breakdown or dealt with some trauma or escaped something. Actually, it’s weird, but one of the things I became aware of is that it’s really valid to look at some things just on the surface, as well as in depth. Some of those things are just enjoyable, because they do skate a bit on the surface, and it’s about having fun. The people enjoy proselytising for being militia men or swingers, and I sort of enjoy hearing it, and whatever brought them to that can remain tacit. Maybe it’s not that important. I’m basically making a case for superficiality, I think.”

If there is a weakness in his work, it is arguably this, for he doesn’t explore how his subjects come to hold the views they do. And yet, he still manages to make many of them more sympathetic – or at least engagingly human – than most documentary-makers would, a feat made all the more unusual for not being achieved through a conventionally therapeutic route. Does he feel responsible for how his subjects come across?

“Yes, sometimes you have to protect the contributors a little bit. There is a slightly greedy aspect in journalism where you think I’m entitled to everything, and anything they say in an unguarded way is just grist to my mill and fair game. And I think there are limits. You don’t stop being a human being when you start being a journalist.”

He doesn’t altogether rule out revisiting the genre of the celebrity profile documentary at some point, and he has Heather Mills in his sights. It’s not hard to see why from Theroux’s point of view – but not so easy to see what could possibly be in it for her.

“Well, it’s interesting. Some people are interested in raising their profile, some are interested in raising the profile of a project – in her case I think it’s landmines and vegetarianism – and some people just want to get their point across. What’s in it for her is that her public image could really use some freshening up. Don’t you think?” I’ve got a feeling, I say, that it could only make matters worse for her.

“Really?” he says, pulling a classic Theroux face of puzzlement, and just for once I’m not convinced he’s being entirely truthful. “I think actually it might make it better.”

But that, I laugh, is because he wants it to happen! I imagine most people reading this will think Mills is bananas, and if she spends time with Theroux she’s won’t look any less bananas. So we’re back to this question of disingenuity; he can’t seriously believe her profile would be improved, can he? “I said it could use some freshening up,” he smiles, and we both laugh. I don’t see, I tell him, how a documentary could have a successful outcome for her.

“You might be right,” he concedes. “And that would weigh against doing it.” Seriously? “Yeah, it really would.” So if he can’t see any plausible possibility of a film being of some benefit to a subject, he wouldn’t want to make it? “Oh, absolutely. Definitely. What, to go in there thinking I’m going to turn someone over?” He looks mildly appalled. “Well, that’s bad faith, isn’t it?”

I wouldn’t be surprised if he has become more concerned with the ethics of documentary journalism as he has grown older. The son of the travel writer Paul Theroux, and younger brother of the novelist Marcel, he was only 22 when he began working for Michael Moore on an American documentary series, and was still in his mid-20s when the BBC commissioned his first series of Weird Weekends. Growing up in his family, “There was a kind of snobbery about books being better than everything; books were considered the acme of everything the human mind has to offer,” and he has described his family as competitive, so he must have felt some pressure to make a quick success of his TV career.

But now arguably the most famous member of his family, at 40 he can probably afford to approach his work with more gravitas. He lives with his partner Nancy Strang, a TV director, and their two young sons, and says that one of the surprises of fatherhood has been the requirement to exercise authority. “I think I’ve drifted through life not having to have any position of real authority, so to have to be the disciplinarian is quite different for me.” They live in the notoriously unlovely north London neighbourhood of Harlesden, and he admits a little shamefacedly that another change brought about by parenthood has been “really bourgeois concerns about the quality of your neighbourhood. Quality-of-life issues, littering, noise, that sort of thing.” Harlesden is not exactly overpopulated by celebrities, though, and “more by accident than design” he has become its unofficial famous face, so it would feel a bit of betrayal to him to move somewhere leafier.

“There is an element of that,” he grins. “But I’m slightly embarrassed about it. I don’t think you should take those responsibilities too seriously, because that way madness lies. Like the fate of a London suburb hinges on my house choices.” He raises his eyebrows in self-mocking horror, and laughs at himself. “I mean, I don’t think so.”