Stuck On You: The Football

Sticker Story

ITV1

“This comes from the producer who made the terrific Get Shirty doc, and it’s just as enjoyable” – Radio Times

Reviews

This comes from the producer who made the terrific Get Shirty doc, and it’s just as enjoyable. We revisit the golden age of football stickers, launched by newsagent Giuseppe Panini from his kiosk in 1960s Modena. Middle-aged men recall the swapping frenzy: one remembers exchanging an Airfix model of the Graf Spee battleship for a George Best sticker. The early glue-in versions were hilariously bad, but it grew to be a multimillion-pound business.

Searching down into the nether regions of your EPG (electronic programme guide) isn’t always an exercise in resigned futility. Just occasionally there be TV treasures down there, squashed into the wall of listing-blocks a few tiers above repeats of Ninja Warrior on Challenge or Beavers in Vegas on Babestation TV. Take last night. If you hadn’t surfed down the listings you might have missed the fantastic little story told in ITV4’s Stuck on You: The Football Sticker Story.

Here was a history of the football-sticker album that wasn’t simply an I Love the 70s-type laff at memories of going “got … got … need” in the playground – although there was quite a bit of that, and the programme’s basic style did insist on incessant signposting on the soundtrack.

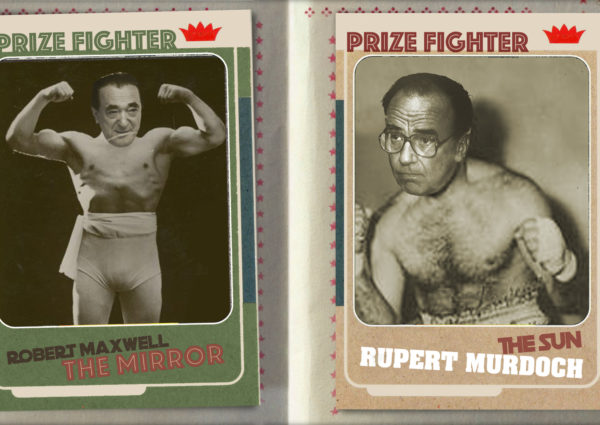

But although nostalgia was in the passenger seat – one man recalled selling his Airfix battleship for a George Best sticker – driving the programme was an unfamiliar tale of how the humble sticker became a multimillion pound slugfest between Robert Maxwell and Rupert Murdoch.

Four of the men at the heart of the craze recalled it all. How The Sun’s shy and retiring editor Kelvin MacKenzie threw his wallet on the table at Panini’s offices in Italy to win its business. How Maxwell went one better and bought the company outright, before showing a talent for sucking all the joy out of the national act of placing stickers in dog-eared albums.

And so the four Panini employees were cast as David to Goliath, setting up a rival group, Merlin Publishing, which Maxwell set about crushing by holding its distributors to ransom. The saga had a happy ending: Maxwell was soon overboard, while Merlin survived, flourished, then made a packet by selling out for $50 million.

There’s surely a movie to be made about this – a quirky hobby causing mayhem among media titans. All down to the strange magic of opening a sticker packet outside the newsagent to see if Kenny Dalglish was inside.

A simple pleasure in a complicated world this week: stickers. ITV4’s Tuesday night documentary Stuck On You tells a story of collectible cards that begins in an newsagents in northern Italy and becomes a playground obsession around the world and, in the UK, a theatre of conflict in the great 1980s tabloid war between Robert Maxwell and Rupert Murdoch.

Like the humble sticker, this film has rather unpromising beginnings as four English chaps in late middle-age with job titles like ‘Sales Director at WH Smith’ explain how they came to be the British retail arm of Panini Stickers.

Wait! Come back. It gets good. Giuseppe Panini began selling collectable cards from his shop in Modena and soon had a name almost as famous as the city’s Ferrari and certainly with more affordable product lines. Then some sticky smarty came up with the idea of adhesive. In 1970, they began doing World Cup albums, and throughout the next decade, albums for football leagues around Europe. In 1978, in association with Shoot magazine, Panini began in the UK. They would sell millions.

Just looking at that yellow letterbox-shaped logo of a jousting knight and the red typeface of Panini functions as a Proustian madeleine for many who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s; immediately transported back to a playground of “Got, got, need” and painstakingly cataloguing, sticking, yearning for a shiny sticker of the Liverpool badge or whatever was that year’s white whale.

Ryan Giggs, no less, pops up to say: “Kids with big bundles of stickers saying, ‘Have you got this one, have you got that one, I’ll swap you this, I’ll swap you that.’ Trying to fill your book was huge.

“And yeah, I never managed to fill my book.” He says that he did make it on to the cover of one, but considers this a poor second prize.

For the company, Smash Hits followed and then a Royal Family album. Sales director Peter Warsop claims that the Royal book benefited from the keen eye of an unlikely proofreader: “The Queen noticed there was an error with the information about one of the [horse-drawn] coaches,” he says. “Buckingham Palace wrote to request that the error be changed.”

By the late 1980s, both The Sun and The Mirror wanted a piece of the action. Panini in Italy decided to go with Murdoch. “Maxwell was apparently livid,” says Warsop. Maxwell then made the Italian parent company an offer they couldn’t refuse. He bought up Panini. The British arm decided to go it alone with a new business, Merlin stickers. That in turn drew the wrath of Bob, who unleashed sticker hell via a deluge of writs, as well as bullying the new firm’s suppliers and wholesalers to ditch the smaller rival.

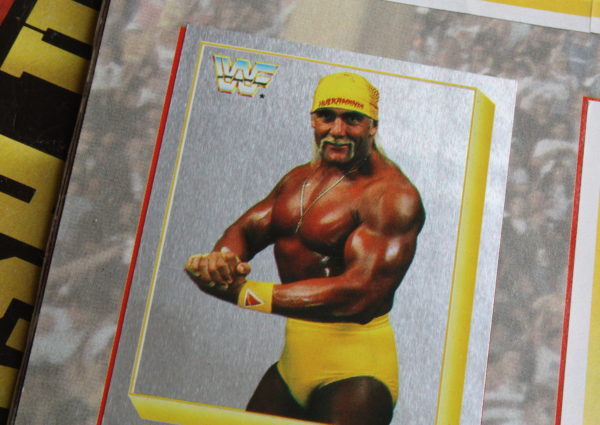

Stickers, it turned out, could be a dirty business. Houses were remortgaged, careers and livelihoods were on the line and the situation was sticky indeed for the Merlin boys until an improbable saviour arrived in the form of WWF (wrestling, not pandas).

That ludicrous product enjoyed a bit of a moment in the early 1990s for UK youngsters and, via a sticker collection and merchandising operation out of that, Merlin survived. It even bloomed into a number of new collections, up to and including one on the Desert Storm invasion of Kuwait. Stickers’ world domination was complete.

This is a very enjoyable little yarn about a small British business separating from a European parent and making the best of it in a hostile environment.

Perhaps we could swap them for our current politicians?

If you were a child whose eyes lit up when seeing a shiny foil badge in your newly opened packet of stickers or maybe someone who has rekindled your craving for collecting in adult life then Stuck on You, which airs at 10.15pm tonight on ITV4 is a must watch.

The hour-long documentary charts the history of football stickers in the UK, those bundles of self-adhesive joy which have given so much pleasure to both children and adults alike in the years since Panini’s emphatic arrival on these shores in the 1970s.

But this isn’t simply an excuse for an overdose of nostalgia or just an opportunity to reminisce about those heady days of swapping stickers with friends and classmates; Stuck on You charts the fascinating story of how a product which was initially used as a gimmick to sell bubble gum became one of the biggest and most lucrative industries going.

Thanks to some fascinating archive footage, along with first-hand accounts from those who were there from the start, this is the tale of how the humble football sticker progressed from a passive playground pursuit to a multi-billion pound industry, ultimately ending in one of the biggest boardroom battles between two Titans of the tabloid world in the late 1980s.

With contributions from the likes of celebrity collector Ryan Giggs as well as a number of fellow sticker superfans, including Greg Landsdowne whose book of the same name was published in 2015, we are treated to a fascinating insight into how the phrase, “Got, not got, need,” entered the vocabulary of football fans everywhere

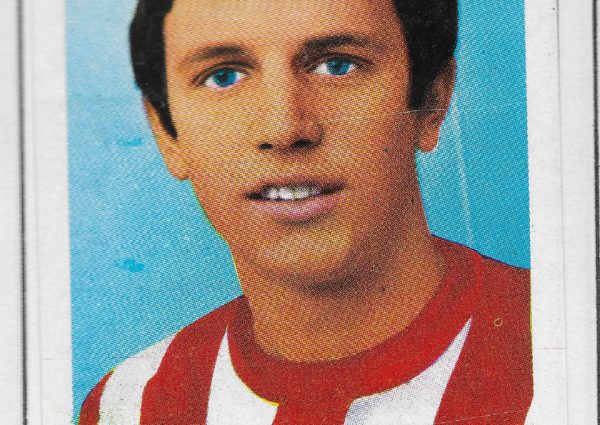

What’s shocking when watching the programme is the poor quality of football cards and stickers available in Britain prior to Panini’s intervention in the mid-1970s, as children were left to battle-it-out over a mish-mash of various incarnations that often had been coloured in by hand and had to be stuck into shabby albums using PVA glue.

Of course, that was before four brothers from Modena invested in large-scale sticker making machinery prior to their expansion into the British market in the 1970s, culminating in the launch of Football ’78 which was the spark that lead to the sticker explosion; mostly thanks to a clever piece of marketing which saw albums and stickers given away free in Shoot magazine and by the mid-1980s it was estimated that some 90% of children were collecting Panini football stickers.

Such success soon attracted the attention of some of the biggest players in the publishing industry and, after a bitter battle between the two biggest selling newspapers of the time, The Sun and The Daily Mirror, the Panini brothers decided to sell up to media mogul Robert Maxwell – a decision which ushered in something of a sea change in the football sticker market.

As a result, the four men at the heart of the UK sticker craze – Kelvyn Gardner, Peter Warsop, Mark Hillier, and Peter Dunk – decided to jump ship and take on the mighty Panini by setting up rival firm Merlin and venturing into the world of music, wrestling and even royalty as the two companies vied to corner the collectables market.

Documenting a story that has more twists and turns than a George Best dribble Stuck on You brilliantly depicts how the newly formed Merlin overcame all the odds – thanks in part to the likes of Hulk Hogan and Hacksaw Jim Duggan – to become the official partner of the newly formed Premier League, while Panini’s future was thrown into doubt following the death of Robert Maxwell in the early 1990s – only to be revived again some years later before selling tens of millions of stickers during the World Cup of 2014.

A thoroughly enjoyable watch this light-hearted yet informative documentary brilliantly blends a fascinating story with a hearty dose of nostalgia in equal measure which anyone who has ever collected football stickers, avid or otherwise, will definitely be glued to.

‘Shinies’, playground ‘swapsies’ and a cult following: The story of how football stickers took over the world

For the generations who assembled those meticulous sticker album collections, Panini is a name synonymous with schoolyard swaps, ‘shinies’ and the company’s heraldic knight insignia. It takes a collector of the very obsessive kind to know about the comical glitch on the Celtic pages of the 1978 edition.

That particular album has sat on your correspondent’s shelves for the past 39 years, but Greg Lansdowne takes fewer than 10 seconds to point out — with no advance notice we’ll be discussing the edition — that the head of Johannes Edvaldsson, the Icelandic centre back, is superimposed onto the shoulders of Paul Wilson, the club’s forward, on page 52.

It was Panini’s first football album in this country, and was ‘very rushed’, says Lansdowne, a collector turned sticker historian, and indeed the Edvaldsson sticker — employing rudimentary means to disguise that Panini lacked an image of the defender in a Celtic shirt — really does look ridiculous, now that he comes to mention it.

Panini did not look back. By the time they published their 1979 annual, capturing the Football League and Scottish League squads for the 1978-79 season, they were employing 21st century methods.

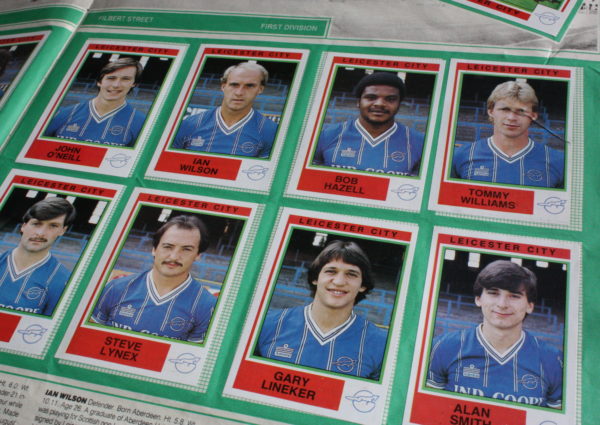

The Italian firm struck commercial deals with the Professional Footballers’ Association and Football League, guaranteeing access which enabled them to deliver on what became their article of faith – photographs of every first-team player at every club, in that season’s kit.

The true Panini devotees, like Lansdowne, will tell you that 1979 was the most sublime of all because the much-coveted foil team badges — ‘shinies’ — were enhanced and had a silk-like texture. ‘It seemed to be expensive, so it was back to ordinary foil badges by 1980,’ Lansdowne says.

Others swear blind there will never be a Panini album like 1983, the year in which all players were displayed in full strip. Alan Curtis chose to be photographed in kit and carpet slippers and Bob Latchford didn’t bother with any footwear, which persuaded Panini to revert to head shots in 1984. ‘1983 was a particular favourite of those who like kits,’ Lansdowne says.

These idiosyncrasies did not prevent the Panini albums becoming a commercial phenomenon by the early-1980s. So much so that they triggered a bitter war between Robert Maxwell’s Daily Mirror – who struck a promotional deal to offer readers a free album and stickers – and the Sun, who promptly sought to grab it off them.

The Sun’s editor Kelvin McKenzie was so intent that he arrived in person at Panini’s head office in Modena and theatrically threw his wallet across the desk during negotiations. He got his way. Panini was selling nearly 100 million packets a year at the time.

Within five years Maxwell would exact the ultimate revenge. Obsessed by Panini, he bought the company, took its £15m cash reserves and brought it to its knees within a further four years.

These developments and many more form the dramatic core of a documentary on ITV4 later this month, which draws on Lansdowne’s book about the company, Stuck on You, which was published two years ago.

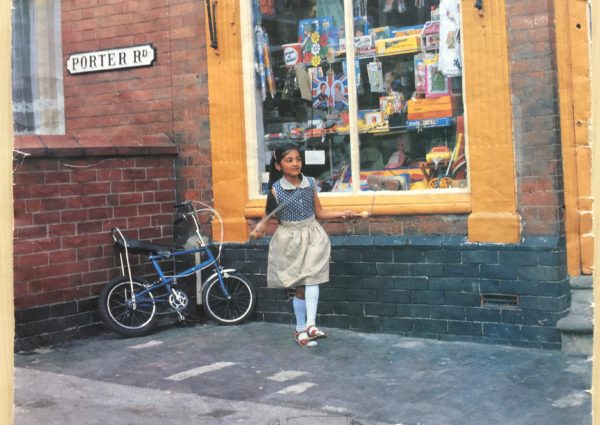

Both film and book relate how Italian brothers Benito and Giuseppe Panini started out in business with a newsstand at Modena in northern Italy, branched out into newspaper distribution and stumbled on a sticker craze in 1960 by unexpectedly managing to shift three million packets of two stickers, depicting flowers and plants.

They moved into Italian football stickers a year later, then hit upon the idea of an accompanying album for the 1970 World Cup. but it was not until a relaxation in European trading laws that a full offensive was launched on the UK market.

A British company, FKS, was trying something similar at the time but most of its albums involved the fiddly process of gluing stickers in and Panini immediately blew them away. Their quality was superior but the firm also tied up countless distribution deals to ensure that its albums and stickers were everywhere for Euro Football 77 — its first title here.

It helped that Shoot! magazine saw the opportunity. Its own sales soared to 600,000 when it gave away a free album and one 30p packet of six stickers of the 1977 album. (Panini always published in January, giving it the five months it felt it needed after the clubs’ pre-season photo-shoots to assemble squads, in correct strip, with accompanying text. There was an obsession about accuracy.)

The documentary charts Panini’s British spin-offs, including Smash Hits sticker albums in the 1980s and a Royal Family album, but football was the staple, with newspapers’ sometimes hapless attempts to copy Panini creating a comical sub-plot.

The bedrock of the Panini operation were its ‘Fifimatic’ sorting machines which sorted and packaged random sequences of six stickers.

Lacking this technology, the Daily Mirror employed prison inmates to put six stickers into packets for its own 1986-87 ‘Stick with Soccer’ annual. Collectors would open packets to find they were one or two stickers short, and even if they had the full complement, many found the same sequence of players had been repeatedly stuffed in.

There was nowhere to stick Steve Gritt of Charlton in another Mirror album. In the album for the 1980-81 season the Daily Star got off the ground with a wrongly captioned photograph which meant the face of Aston Villa’s Des Bremner beamed out from the Gordon Cowans sticker. To compound things, the real Des Bremner was designated the adjacent slot to Cowans, so there were very obviously two Bremners.

The newspapers’ struggles only went to show how difficult the business of producing a quality album actually was. Commercially, none of these ad hoc efforts could get close to Panini.

Maxwell discovered that it was not as easy as it looked when he purchased the firm in 1987 for what was thought to be £96m. The company was still flourishing at the time but Benito had died the previous year and his brothers preferred fast cars and holidays to First Division team groups.

The Panini British management team’s attempts to buy-out the company stood no chance in the face of what, at the time, seemed to be immense Maxwell commercial might.

When the same executives set up a rival firm – Merlin – and launched a rival ‘Team 90’ Football League album, Maxwell threatened wholesale distributors that he would withdraw the Mirror from their warehouses if they distributed of the new outfit’s product. It was a disaster for the fledgling firm, which found unexpected salvation by publishing World Wrestling Foundation albums.

It was all a smokescreen, of course. Maxwell was a busted flush. He installed a chief executive at Panini who was so disastrous that the management team walked out en masse. The firm was haemorrhaging money by the time Maxwell was found dead at sea on November 5, 1991.

Merlin went on to dominate British domestic football stickers in the Premier League era. Its executives found an ally in Arsenal vice-chairman David Dein, who was instrumental in the league’s foundation, and helped them get an official Premier League sticker album deal.

Merlin reached the old Panini levels, shifting 76m packets in the Premier League’s early years, while Panini’s last British domestic album dived to sales of no more than three to four million packets, in 1990.

The company’s 2014 World Cup album was its biggest-selling ever worldwide, with British collectors buying in huge numbers. Total sales from the album were an estimated £3.5m. Panini is expected to be the only serious player in the lucrative UK market for the 2018 World Cup as England rights have been acquired for the first time.

The big question in the world of stickers is whether it will use its dominant position to increase the price of cards from 50p to 60p for a packet.

There’s an industry view that it’s a lot to charge for a firm that did thrive on good value in its golden British era. Lansdowne is among those who reject the cynics’ notion that the much-needed last few players for an album were deliberately kept out of circulation to increase sales, back in the 1980s.

‘There was a scarcity of some cards,’ he says. ‘Some Liverpool stickers were impossible to get. That was because if people got Liverpool doubles, they’d stick them on their school folders or their bedroom walls. That’s how successful the team was, but Panini seemed to know that collectors have to believe there’s a chance of finishing the album. I don’t believe cards were kept out of circulation.’

It did not cost a fortune to complete a collection back then. Panini would add a maximum of 50 stickers, including no more than five ‘shinies’, to those who sent near-completed albums in. In 1978, they charged 2p per sticker including postage for this and it was one album per household address, though no one ever knew if they checked.

Few receiving the returned complete set would have noticed the very rare glitches which also included some of the Liverpool players being pictured in crewneck tops in 1978, when the official Umbro kit that year was V-neck.

‘The flaws have seemed more iconic with the passing of the years,’ says Lansdowne. ‘The albums were formulaic and when you look back now, there’s a cult element about an error. It makes them even more wonderful.’