Two Tribes: How Football Saved a City

BT Sport

“In just 81 minutes of spellbinding airtime director Andy Wells captured a remarkable snapshot in time” – Liverpool Echo

Reviews

Two Tribes – How Everton and Liverpool allowed a city to walk tall in a time when it was on its knees

By David Prentice

It really was the most incredible contrast.

Bleak but buoyant. Wretched but reborn.

It was the 1980s when one in five of Liverpool’s population was unemployed. There were riots on the streets of Toxteth. And the incumbent Tory government had even discussed the “managed decline” of the city.

Yet on the football field Merseyside ruled, Liverpool bands dominated the pop charts and Mersey playwrights crafted some of the most memorable dramas ever written.

It really was the best of times and the worst of times.

And it is an era captured in an evocative, poignant and stirring BT Sports documentary “Two Tribes – How Football Saved a City”, premiered at 9pm on BT Sport 1 tonight.

In just 81 minutes of spellbinding airtime director Andy Wells and executive producer Caj Sohal have captured a remarkable snapshot in time – as told by the people who lived it.

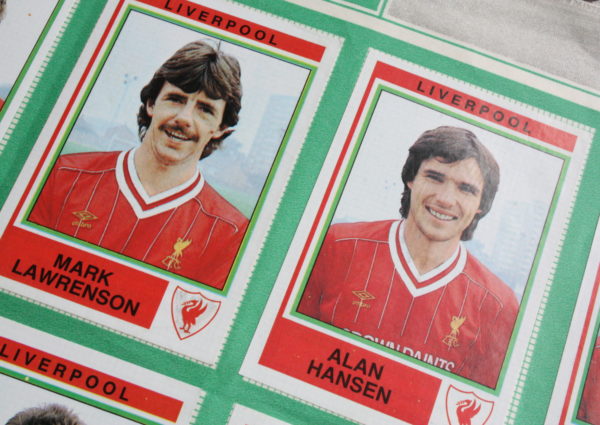

The football stories are told by the players who created them – Peter Reid and Graeme Sharp from the blue half, Steve McMahon and Mark Lawrenson from the Reds.

Indicative of the time, even within their stories there are contrasts.

“I can’t be disingenuous and say I saw the issues on a day to day basis,” says Lawrenson with typically honesty. “I didn’t. Like a lot of players I lived out towards Southport. You would go to training and be cocooned from it all. I didn’t have a Scooby Doo what was happening”

But team-mate McMahon said: “I was aware because I was brought up in Halewood right in the heart of things. I can’t remember my dad working to be honest. He used to tell people he was a scaffolder but I never saw him go out to work.

“I think people were hiding what was going on in the background. Imagine Liverpool without that football success? I think football dragged people through it. It dragged me through it because I wanted to get out of that system.” David Morrissey gives a thespian viewpoint, while Pete Wylie, perhaps Liverpool’s greatest living loyalist and advocate – a man so devoted to the city he even named his daughter Mersey – and The Farm’s Pete Hooton – eloquently tell the musicians’ story.

But all of the storytellers are welded to football. All are fans first, actors, singers and performers second.

Then there’s the politics. The first slice of humour which permeates this drama throughout is uttered in the opening few minutes. A narrator looking across at the city’s waterfront skyscape from a ferry recites: “ ‘I’m gonna be someone, I am’ … says every kid in Liverpool in living memory. Some make records. Some break records. Some break windows. Some become footballers or actors or both. Others write plays and poems and become painters and decorators …… while a few have no talent at all and turn to crime – or politics.”

Cue the first of many telling recollections and observations from former deputy leader of the city council, Derek Hatton, all delivered with his trademark gusto. Thirty-five years has not dimmed this ardent Evertonian’s passion and enthusiasm one iota.

Lord Heseltine, formerly the Minister for Merseyside, is equally eloquent, then there are contributions from Hillsborough Justice Campaigner Sheila Coleman, Reds fan Eddie Singleton – and Cheryl Varley, colourfully introduced as “activist.” But through the riots, the protests and the job losses, through 18 Scouse bands in the top 40 and through astonishingly powerful TV dramas like Boys From The BlackStuff – runs the rich pageant of football.

“It’s the tale today of two great clubs but one extraordinary city,” says Desmond Lynam introducing another Wembley showpiece featuring Everton and Liverpool – one of FIVE which took place between 1984 and 1989.

At one of those finals fans are pictured actually risking their lives to try and gain access to the stadium.

But football has always mattered on Merseyside.

In the 1980s it possibly mattered more than ever before.

During that era a working class population stood up to a manifestly unfair and provocative Conservative government and bit back.

And they did so with football providing a rich source of pride in their derided city. Simon Green, the head of BT Sport who commissioned the documentary, said: “Two Tribes is a thought-provoking examination of how football transcends sport and becomes central to wider society.” It does all that, but it entertains too.

There is humour – and pathos, and archive footage from the era both on and off the pitch. Derek Hatton delivers the most poignant pay-off line, from the balcony of the Town Hall, wistfully looking down where he once addressed 50,000 Scousers attending a mass protest.

“I wonder what it would have been like in the city if everything was going against us politically, as it was, and the teams hadn’t been doing well?” he says, with uncharacteristic softness. “I mean it’s hard to imagine but that would have been even more devastating for the city.

“What actually kept people going was that they knew that the football teams were the best in the world, whether they were blue or red. “Can you just imagine all that devastation happening … and no football victories? “That would have been frightening.” Fortunately we didn’t get to find out.

Two Tribes: powerful documentary lovingly captures spirit of defiance in Liverpool in the 1980s

Alan Tyers

The most powerful stories are the ones we tell to ourselves, about ourselves. Two Tribes, BT Sport’s Saturday night documentary about the city of Liverpool and its two famous football clubs functions as a love letter from the city to itself.

The Liverpool of the film is rich in talent, rebellious, defiant, united, wronged. There can be no argument about the first point. With the Beatles, all those league titles, Alan Bleasdale, Merseyside could put its music, football and drama history of the second half of the 20th century up against anyone anywhere. The fourth pillar of the city’s life as portrayed by the film, its politics, will be more contentious for some viewers.

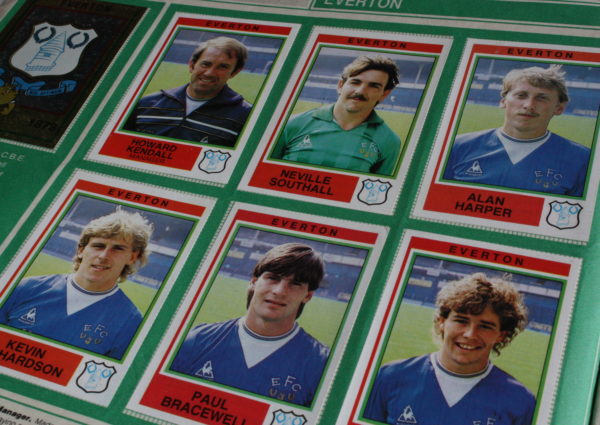

Derek Hatton, garrulous and freakishly youthful-looking at 71, marauds unstoppably through the film just as Peter Reid – another contributor – once did through First Division midfields, and post-match refreshments.

The one-time Trotskyite deputy leader of the Liverpool council that defied Margaret Thatcher’s government in the budget-overspend rate rebellion, and famously hired taxis to deliver redundancy notices to council workers, is given pretty much a free role throughout, and it is not going to be everybody’s cup of tea, you have to say.

Hatton, and the film, tell a great yarn. The decline of industry in the North was not peculiar to Liverpool, but the argument is made that Liverpool was singled out for particularly heartless abandonment, for Geoffrey Howe’s “managed decline”. The results were poverty, the Toxteth Riots, signing on, but also a radicalism and the seedbed for working-class creativity and cultural risk-taking.

As David Morrissey, whose star was born in Willy Russell’s 1983 ‘One Summer’ TV drama, says: “There was no such thing as a safe job, so going into the arts was no more of a risk than anything else.”

And throughout all this upheaval and poverty, the film says, there was football. The two finest teams in Britain providing a beacon, an escape, a source of pride throughout the 1980s. Mark Lawrenson and Graeme Sharp are among the Liverpool and Everton greats who make superb observations about what made the place, and its football so special. There are warm and funny recollections from fans about the famous Merseyside cup finals, about a rivalry which is often characterised as being sibling or affectionate rather than warring and spiteful.

If the film could be accused of putting forward a somewhat uncritical or sentimental view of Merseyside, then Liverpool people might very well argue that it is merely one drop versus a tide of negativity, snobbery and spite that has flowed the other way.

Sheila Coleman, who campaigned so long for the Hillsborough families makes explicit the continuity, as she perceives it, between sneering at Scousers, Harry Enfield’s sketches, and dehumanising, and the callous behaviour from South Yorkshire Police and the death of 96 people at a football match, and the coverage of that tragedy in some sections of the media. “Stereotypes,” she says, “can have disastrous consequences.”

In the 1980s, Britain’s bitter divisions were between right and left, and perhaps between North and South. Today’s are more of a culture war, synthesised and reductively boiled down into Leave and Remain by people who should have known better, a conflict that is not geographic or containable within the failed system of party politics but to do with values and identities, those looking forward to those feeling left behind.

Football, for its faults, does remain some sort of uniting force; perhaps sporting glory will return to Liverpool or Everton one day soon. It will be fascinating indeed to see what stories those who love those clubs, and that city, tell themselves about it all this time around.

Two Tribes: Political unrest and tragedy scarred Merseyside in the 80s, but on the field Liverpool and Everton were unbeatable

A new film, Two Tribes, tells the tale of Liverpool the city in the 1980s

Merseyside was scarred by riots, political unrest and economic decline

But its football clubs, Liverpool and Everton, won the league eight out of 10 years

Everton’s Peter Reid and Liverpool’s Mark Lawrenson recall how it unfolded

A new film, Two Tribes, premieres this week, telling the tale of Liverpool in the 1980s.

Scarred by riots, political unrest and economic decline, the city was in turmoil and on collision course with the Government. Amid this troubled backdrop rose two football teams.

Liverpool and Everton dominated the domestic and European game, offering Liverpudlians fresh hope and an identity.

The league title stayed on Merseyside for eight out of 10 years but then, in tragic circumstances, the sport that had given its people a voice shook the city through disasters at Heysel and Hillsborough.

Here, Sportsmail recalls how the decade unfolded with two of the film’s contributors, Everton’s Peter Reid and Liverpool’s Mark Lawrenson…

Peter Reid, Everton midfielder, 1982-89

Unemployment had ripped the heart out of Liverpool when I signed for Everton in 1982. You couldn’t ignore the political landscape. I’d grown up in Huyton where Harold Wilson, the former Labour Prime Minister, was my MP. It’s fair to say we weren’t great lovers of Margaret Thatcher’s government. There’d been riots the year before, companies were closing down, my dad Peter’s job had been affected, my brother Michael had to join the Merchant Navy and my other brother Gary went down south for work. It was difficult.

But Liverpool is a city of strong opinions and it began to bite back. There was great music, the comedians were sharp and there was Derek Hatton. Derek was a left winger, not in Kevin Sheedy terms, but the Labour movement. He wasn’t even popular in his own party but he was passionate about his beliefs and one happened to be Everton. We struck up a rapport over a few drinks in town where he spoke eloquently about his love for the club and its importance to fans.

One night we were having a drink with Adrian Heath and his dad, and Derek promised to get Adrian mentioned on Question Time. Sure enough, in the heat of a political debate, Adrian’s name pops up. But Derek had a point. Football had become an emotional crutch for supporters whose lives were in a downward spiral.

Liverpool were in their pomp and Everton had been in the doldrums. Howard Kendall was under extreme pressure when the FA Cup came round in 1984 and we were away to Stoke City. Howard opened the slats of the window in that Victoria Ground dressing room and said: ‘Just listen to that.’ All you could hear was this wall of noise from our fans. That made us feel 10 feet tall.

They gave us the confidence and we fed off that to become a good team. We couldn’t believe how half of them got into Wembley for the Milk Cup final against Liverpool. Climbing roofs, sneaking in vans, scaling walls. The game wasn’t much and it lashed down with rain but I can remember welling up seeing reds and blues walking across Wembley Way and afterwards when the whole stadium sang ‘Merseyside’.

Whether it was a cry of defiance, unity — whatever, it was powerful. It was a broken city shouting it was proud.

When we got to the FA Cup semi-final against Southampton at Highbury, it was absolutely packed with Evertonians. Every vantage point was blue. It was electric and we said to each other: ‘We daren’t come off this pitch without winning.’

Claiming that first trophy, the FA Cup against Watford, was the best feeling. Seeing Howard’s broad smile that day will never leave me. He knew it was the watershed moment. Standing in The Quiet Man pub back in Huyton with my dad surrounded by reds felt fantastic. I was a winner.

The following year, we did a Cup final song, Here We Go, and turned up at the recording studio in party mood. The studio told us that we couldn’t go on unless we took it seriously, so we refused and cracked open a few drinks.

Next thing they relented and one of my mates from school, John Fargin, is on the record as only him and Paul Bracewell were fit to do any singing.

Some fans who were our mates even ended up on Terry Wogan’s show in tracksuits singing at the back.

That bond we formed wasn’t just of the moment, it was for life. Brian Clough said Everton should have dominated the 90s but the ramifications of the Heysel tragedy meant that never happened. As champions in 1985 we knew we would challenge for the European Cup but whatever disappointment we felt had to be put into perspective against the lives that were lost that night.

When Hillsborough happened in ’89, I had joined QPR with Nigel Spackman, who had been at Liverpool. I’ll never forget that day. We were playing Middlesbrough and Don Howe the coach pulled Nige and me at half-time to say: ‘It looks like there’s been fatalities at Hillsborough, do you want to carry on?’ We finished the game then took in what was happening on TV, devastated. I knew Everton fans had been leaving their semi-final against Norwich at Villa Park to check on family and friends.

In the week afterwards, Nige and I went up to Anfield to see Kenny Dalglish and Alan Hansen. What I saw was heartbreaking, the messages, the flowers and what hit me was the number of blue scarves tied across the ground.

That our two teams should play that year’s Cup final was only fitting. On the eve of the game we bumped into some fans at the Royal Lancaster Hotel and I offered to get a round in for the three or four who were there and put it on my room. The next morning I came down, got the bill and it was £2,000 for drinks. The cheeky sods had obviously got my number and had a good night on it. But hey, if anyone deserved it, they did.

Peter Reid was talking to Simon Jones

Mark Lawrenson, Liverpool defender, 1981-88

Talk about a different world. In 1981, when I was playing for Brighton, I lived close to our training ground in leafy Hove. I had an old English sheepdog at the time called Barnaby and every morning I’d walk through the park to work with him. Barnaby would stay in the office while I trained, then afterwards we’d head home via the same route.

It’s fair to say I couldn’t do the same when I moved to Liverpool. Having been on the south coast, I hadn’t fully appreciated the social problems Liverpool as a city had encountered and it would become worse in 1981 when the riots in Toxteth erupted. For a footballer whose transfer fee was almost £1million, it made you think.

I can’t be disingenuous and say I saw the issues on a day-to-day basis. I didn’t. Like a lot of the players from both clubs, I lived out towards Southport. You would go to training and be cocooned from it all. Not once did I think I’d made the wrong move. I had to contend with being called a ‘Woolly Back’ for the first six months, but as a lad from Preston, I knew I had made the right decision to come back north. As much as I loved Brighton, it felt like I had moved home.

But, even now, little things give you a sense of what it was like. It felt like Anfield was always full but if you ever see old footage, you can see the empty seats — a lot of fans simply couldn’t afford to get to matches. The one thing Liverpool and Everton provided, however, was escapism. You knew on Saturday afternoon that many of the crowd would have scrimped a bit of money together and you were left in no doubt exactly what football meant to them.

It was an incredible time. We were going at it hammer and tongs with Everton for much of the decade but the rivalry on the pitch brought camaraderie off it. I lived near Everton’s Graeme Sharp and Pat van den Hauwe and we would see each other out and about. What really sums the period up for me was the 1984 League Cup final at Wembley.

It was the first time the clubs had played each other for a trophy — the first final played on a Sunday — and I think there were concerns in London about the mass movement of 100,000 coming down from the north. The people of Liverpool had been battered, cut adrift by the Government, and the Met Police were braced for the two clubs being in London. But there wasn’t a murmur of trouble. There was a show of solidarity and the fans showed the world they came from a proper city.

Unfortunately, the game didn’t live up to expectations. Dear me, it was terrible and thank God VAR wasn’t in play then. Alan Robinson, who refereed the game, must have been the only person in the stadium who didn’t see Alan Hansen handle a shot that was going in from Adrian Heath. Afterwards, as the teams walked around the pitch and the crowd were chanting ‘Merseyside’, we all got together and there was an impromptu photo of red and blue shirts alongside each other.

I think that summed everything up. Two proper clubs, two proper teams and one proper city.

Mark Lawrenson was talking to Dominic King

EXCLUSIVE: In a new TV film, McMahon recalls how Everton and Liverpool fought for trophies while their city battled to survive

By Andy Dunn

Steve McMahon is a rare breed — a player who captained both Everton and Liverpool.

A Goodison Park ball boy, who became, at the time, the club’s youngster skipper, and went on to become Kenny Dalglish’s first signing.

When the two tribes meet on Sunday, it is unlikely McMahon will be in attendance. Even after more than three decades, not all the wounds from his journey across Stanley Park – via Aston Villa – have healed.

There might still be some out there, somewhere, who have a romantic perception of Merseyside footballing rivalry. But now – as in McMahon’s heyday – it is just as intense as in any other of the British game’s hotbeds.

The only difference is that Everton were not just occasionally trying to put a spanner in Liverpool’s works –one of the prime objectives at Goodison this Sunday – they were normally vying to be a powerhouse of their own.

For nine seasons from 1981-82, Everton’s finishing positions in Division One read: 8, 7, 7, 1, 2, 1, 4, 8, 6. During that time, they also won an FA Cup and, memorably, a European Cup Winners’ Cup.

Of course, Liverpool’s honours list during that time is mightily more impressive, but, certainly in the mid-1980s, the two were slugging it out on an equal footing.

And the city was dominating English football at a time when it was also under siege.

McMahon, talking at a shoot for the latest in the BT Sport Films series Two Tribes, says: “In a way, that is what kept Liverpool going as a community. It was their release from the day-to-day, grim stuff. Every penny they could get was saved for the match. It helped them through adversity – football was a get-out for people.”

As Margaret Thatcher was re-elected with a thumping majority in 1983, the people of Merseyside – hit by brutal dock closures and unemployment – turned to a hard-left city council.

And Derek Hatton was in the vanguard of the council’s fight against what it saw as a central government policy to allow the city to fall into decline.

Born-Evertonian Hatton recalled: “Thatcher was in power, the docks were shutting down, we were taking on all the battles, but, ironically, at the same time you had Liverpool and Everton winning everything.

“It was a surprise if Liverpool or Everton did not win something — the likes of Steve and the lads were in the town hall for banquets more often than some of the councillors were in for meetings.

“Football was the escape on a Saturday and, because both sides were winning, the escape was even more relevant.”

The film – to premiere on BT Sport 1 on March 30 – might hint at the unifying role of football, but Everton and Liverpool were two tribes then, just as they are now. No one understands that better than McMahon, who left Everton for Villa in 1983, but was back in town two years later… as a Red.

“A lot of my family, particularly my mum’s side, were still Everton-daft — they didn’t drink Carlsberg because it was associated with Liverpool [as shirt sponsors],” he said.

“In my third game for Liverpool, I scored in the derby. It was my first game at Goodison in a Liverpool shirt. We won 3-2 and, of course, I celebrated. I could not have dreamt of it going any better. You get brought in by Kenny and you’ve got to take on the mantle of Graeme Souness, so there was a lot of pressure.

“My car got absolutely trashed outside the ground, but, as it happened, it was an Aston Villa one, which I had not yet given back.

“To start with, the hatred was beyond belief and I was a little bit bitter. But it was a wonderful time for me. It was an intense and fearsome rivalry – but it was great.”

Two Tribes, the latest in the award-winning BT Sports Films series, premieres on March 30 on BT Sport 1.

‘At the end of my bed was a soldier with a machine gun’ – Mark Lawrenson’s remarkable memories of the Heysel Disaster

by Kevin Palmer

Mark Lawrenson has given a remarkable account of his experiences of the ill-fated 1985 European Cup final at Heysel Stadium, as his Liverpool team played out a game in the shadow of a disaster that cost the lives of 39 spectators.

In a remarkable interview with Planet Football, former Ireland defender Lawrenson has given a chilling account of an evening that is etched into football infamy, as the match against Juventus was played despite the tragedy that had occurred as a wall collapsed during a fight between rival fans prior to kick-off.

The disaster led to UEFA banning English clubs from European competitions for five years, with Lawrenson offered a graphic snapshot of an evening that ended with him in a hospital bed and being guarded by a soldier carrying a machine gun.

“I have two abiding memories from that night,” he stated. “The first was the Brussels chief of police coming into our dressing room and insisting that despite everything that had happened, we would play the game.

“We found that hard to believe given the fact there were people lying dead on the terraces above us, but he was adamant. We suggested Juventus might not want to play the game, but they were ready to play and we had to prepare to play a European Cup final.

“The police argued that if the game was abandoned, there would be more trouble on the streets outside and for that reason, they wanted the match to proceed, but it was a strange, eerie night.

“You go from hearing the news that fans had died on the terrace above us to being told the match was going ahead and we went through the motions of preparing for a game of football that would be one of the most important we would play in our lives.

“The second memory is the match itself, which lasted less than two minutes for me. I had been carrying a shoulder injury and decided to take a chance on getting through it, but I went to tackle (Michel) Platini and the shoulder popped straight out.”

Lawrenson’s account of what happened confirmed his evening took a twist he could not have predicted, as he ended up under armed guard in hospital.

“This surreal, ugly night had taken another unexpected turn. I was taken to the hospital and then things got even more bizarre,” he continued.

“I was still in my Liverpool kit and we get to this hospital and the ambulance backs up to what I can best describe as an area that looks like a supermarket holding bay and I’m dragged into the hospital.

“There I am in my full Liverpool kit, my boots still on, tie-ups for my shin pads and surrounding me in the hospital are the dead and the dying Juventus fans. It is a horrific chain of events.

“I’ll never forget what confronted me when I woke up. I was in this hospital bed and all my Liverpool kit had been taken off me. I never saw the kit again, by the way, but that’s a side story.

“As I looked around this hospital ward, I saw 23 empty beds and I was the only one using the ward.

“At the end of my bed was a soldier with a machine gun. He didn’t speak any English, I didn’t speak any Italian, and we looked at each other and realised we were on the same side of the argument.

“The door was bolted locked and this soldier was there to protect me from angry Juventus fans.

“In the morning, Roy Evans (assistant coach) came in with my wife and brought me some clothes. The trouble was, it was a Liverpool tracksuit, so we had to turn it inside out to get me out of this hospital without anyone noticing me. They sneaked us out through a back door. It was quite a story.”

Two Tribes, the latest in the award-winning BT Sports Films series, premieres on March 30 at 9pm on BT Sport 1.