Unreported World: Nigeria’s

Killing Fields

Channel 4

“In village after village, we witness the aftermath of the massacres,

including bodies thrown down wells and blackened patches where human beings

have been burned alive.” – The Guardian

Reviews

Armed with guns and machetes, they were chanting Kill! Kill! Kill!

In this chilling Easter dispatch, PETER OBORNE reports from Nigeria on the terrifying religious hatred between Christians and Muslims – and warns it could spiral into a repeat of the Biafran war which left one million dead.

There was total silence, apart from birdsong, when we entered the village of Kuru Karama. Every building had been burnt or destroyed. There were no villagers in sight, just two or three soldiers at a guard post dozing in the late afternoon sun.

At length, we found a group of young men and women. Did they live here? Yes. Had they been here on the day of the massacre?

No, they knew nothing. Were they Christian or Muslim? Christian. They bent their heads and one woman placed her hand over her mouth.

Finally, we came across Abdullah. He took us to a little square and pointed out some of the wells into which the Christian killers had thrown scores of dead bodies, their heads downwards.

Some of the bodies were so decomposed that they could not be removed. The stench of death seeped out of the wells.

Abdullah pointed to a sewage pit, now covered with concrete blocks. He told us that the attackers had thrown 30 children in, between six months and three years old. This pit was now their unmarked grave.

All around were burnt patches on the ground in the shape of human bodies, where the attackers had hacked down their victims, poured fuel on them, then set them alight.

Abdullah had been away in town on the day of the attack, and returned later to discover that he had lost 13 family members, including his wife.

He broke down as he told us how, when he helped to pull her body out of a well, he saw that her face had been mutilated. He could only recognise her by her clothes.

Later, talking to survivors, all of who had fled to neighbouring towns and villages, we pieced together much of what had happened. At 8.30am rumours circulated of an impending assault.

A meeting of local imams, pastors and community leaders was called at once – but the police and district chief dismissed their fears. At around 10.30am three vans parked outside the village and gangs of young men, and some women, emerged.

Their faces ware painted red and they were chanting ‘kill, kill, kill’. Far from intervening, the local policemen, so we were told, joined in.

Armed with guns and machetes, the mob went systematically from house to house. At 6.30pm, about the time of sunset, a whistle was blown and the killers obediently got back into their vans, leaving more than 170 dead and others horribly mutilated. There have been no arrests, and no charges have been pressed.

Kuru Karama is a half-an-hour drive south of the Nigerian town of Jos, which used to be remembered (in Westminster at least) for a special reason. A young John Major worked as a bank clerk here in the early Sixties, before a bad car accident forced him to return to Britain and take up politics.

Indeed, Bruce Anderson, biographer of the former prime minister, records that ‘the hill country around Jos is one of the more attractive parts of Nigeria.

The people and the way of life in no way resembled the chaos, squalor and corruption of Lagos, while the bush, the skies and the African landscape worked their magic on John Major’.

Today, Jos, the capital of Plateau State, is the epicentre of Nigerian sectarian violence. Nigeria’s population of around 170 million people is more or less evenly divided between Christians in the south and Muslims in the north. It is the deadly misfortune of Jos to find itself on the demarcation line.

Well over 1,000 people have been killed just this year, and there is no prospect at all of the carnage abating.

Director and cameraman Andy Wells and I arrived in the town – advertised in publicity brochures as the ‘home of peace and tourism’ – just after hundreds had been slaughtered during three days of lawless horror.

We found burnt-out and destroyed homes, cars and shops everywhere. Troops patrolled the streets and there was a strict curfew from 6pm.

Graffiti warned of future terror: ‘We are coming back very soon’, ‘Get ready 4 a return match’, ‘We are waiting for you in Jesus’ name’, which was answered by: ‘We shall see – Inshallah.’

Though open violence had abated, we were told of many ‘silent killings’, with Christians assassinated if they strayed into Muslim areas and vice-versa.

Strangers came forward to show us video footage and photographs taken during what everyone called ‘the crisis’. They were indescribably upsetting: naked, castrated males, the blackened and charred body of a two-day-old child and endless skulls hacked open by machetes.

A film of Nigerian soldiers hauling a defenceless man out of from the back of a van, kicking him and shooting him dead, is being widely circulated.

At the Plateau State Specialist Hospital, Dr Golwa Philimon, a surgeon, told us how he hardly slept for three days as he struggled to cope with the casualties. He saved lives to the sound of the machine-gun fire just outside the hospital and with the smell of burning houses in his nostrils.

‘To begin with,’ Dr Golwa told us, ‘the casualties had machete wounds or had been hurt by blunt instruments. But after 12 hours this changed, and many gunshot wounds came in.’

Dr Golwa said the gunshot wounds had been caused by soldiers wearing ‘fake’ uniforms.

Local people told us again and again how they had seen the police and the army resort to indiscriminate killing as they struggled to maintain order – either that or, perhaps more likely, they were simply taking sides.

Both police and army deny any wrongdoing. In all, said Dr Golwa, there were 180 fatalities at his hospital alone. Dr Golwa also told us that casualties were still arriving.

He introduced us to Joshua and Danjuma, two Christian villagers who said they had been ambushed and shot two days earlier in a revenge attack by assailants from the Fulani, a nomadic Muslim tribe. The following day, we drove to their village and found the inhabitants in a state of fear.

The tribal chief told us that the Fulani attacked every night, that they destroyed crops and looted shops, and that a man had been killed nearby two days earlier.

We were told that people were too scared to stay in their own homes, particularly in the nearby village of Dogo, and there was talk that the Felani were amassing for a major attack.

In the backstreets of Jos, we met Yahusa Sani, a local gang leader. He was around 30 years old and was missing his right hand, which had been hacked off by a machete when the politician he was guarding came under attack from a rival gang.

Yahusa told us how during elections he made good money by stuffing ballot boxes, intimidation and other strong-arm tactics.

He had been heavily involved in the fighting, so he told us, protecting his own people. ‘We wanted to stop the police coming into our area to stop them shooting us. That is what the police do,’ he said.

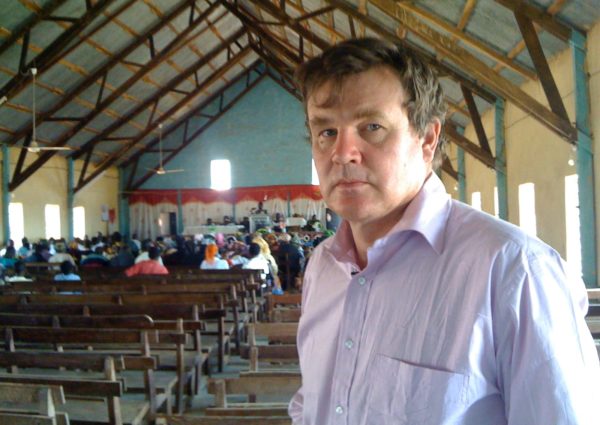

On the Sunday before we left Jos, we returned to Kuru Karama. I wanted to go to church.

Once more, we walked through burnt-out buildings until we reached a large church untouched by the mob. Above the altar were deep red drapes, in front of which a large banner pronounced: ‘Serving God With Purpose.’

Men sat on the right of the church, gorgeously-dressed women on the left.

A soldier with a gun lounged at the back, stretching and yawning. The singing was heartbreakingly beautiful. The pastor intoned: ‘We pray for the peace of the nation, we pray for the people of Nigeria.’

He devoted much of his sermon to reading, with relish, from a long, inflammatory and palpably faked document setting out in great detail Muslim plans to take over and dominate Plateau State. It named leading Muslim generals and politicians as part of an organised conspiracy – Christian Nigeria’s answer to the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

After the service, I sat down with the pastor, the Revd Yohanna Musabot. A smallish man, 42 years old, he told me that he had studied at the Theological College of Northern Nigeria and had been a priest for 10 years.

I asked him whether he apologised on behalf of the Christian Community for the unspeakably evil acts that had been committed just a few yards away from where we were sitting. He refused to do so, saying that there had been crimes on both sides.

So I asked him why all the churches in the village were intact. He could not explain. Nor could he name a member of his congregation who had been killed. I asked him what Jesus would have done. ‘I believe if Jesus were here he would not be happy with what happened’, said the pastor.

I don’t think the pastor was a bad man – he was just caught in a most terrible situation that is way beyond his, or anyone’s, comprehension.

He told me that he had tried to stop the killers, but failed. When I checked this out, witnesses told me that he had been more courageous than he claimed – that he had been head-butted and knocked down, and that if he had not run away he would have been lynched.

It came as no surprise at all to learn of an outbreak of fresh horror just a few days after our return to Britain. This time round the principal victims were the Christians, with 200 dead in the village of Dogo alone. Nobody cares.

When Nigeria secured independence from Britain more than half a century ago, it was hailed as a rainbow nation, like South Africa or Brazil, embracing many different tribes, sects, religions and ethnic identities.

The terrible killings in Jos, and the total inability of the state to halt them or even try to punish the perpetrators, raise troubling questions about the future.

Fifty years ago, when a young John Major worked as a bank clerk in Jos, this kind of horror in eastern Nigeria was the background to what tilted into the Biafran war, which left a million dead.

It’s time to ask how much longer Christian and Muslim tribes can live together in the north, whether history may be starting to repeat itself, and what we can do to help.

They were chanting ‘Kill, kill, kill’

Peter Oborne reports from Jos, a once-peaceful town that has become the front line of a bloody, sectarian war between Muslims and Christians in Nigeria.

There was total silence, apart from birdsong, when we entered the village of Kuru Karama. Every building had been burnt or destroyed. There were no villagers in sight, just two or three soldiers at a guard post dozing in the late afternoon sun.

At length we found a group of young men and women. Did they live here? Yes. Had they been here on the day of the massacre? No, they knew nothing. Were they Christian or Muslim? Christian. They bent their heads and one woman placed her hand over her mouth.

Finally we came across Abdullah. He took us to a little square and pointed out some of the wells into which the Christian killers had thrown scores of dead bodies, head downwards. Some of the bodies were so decomposed that they could not be removed. The stench of death seeped out of the wells. Abdullah pointed to a sewage pit, now covered with concrete blocks. He told us that the attackers had thrown in 30 children, between six months and three years old. This pit was now their unmarked grave. All around were burnt patches on the ground, in the shape of human bodies, where the attackers had hacked down their victims, poured fuel on them, and set them alight.

Abdullah had been away in town on the day of the attack and returned later to discover that he had lost 13 family members, including his wife. He broke down as he told us how, when he helped pull her body out of a well, he saw that her face had been mutilated and he could only recognise her by her clothes.

Later, talking to survivors, all of whom had fled to neighbouring towns and villages, we pieced together much of what had happened. At 8.30 a.m. rumours circulated of an impending assault. At once a meeting of local imams, pastors and community leaders was called – but the police and district chief dismissed the fears.

At around 10.30 a.m. three vans parked outside the village and gangs of young men, and some women, emerged. Their faces were painted red and they were chanting ‘Kill, kill, kill’. Far from intervening, the local policeman, so we were told, joined in. Armed with guns and machetes, the mob went systematically from house to house. At 6.30 p.m. , about the time of sunset, a whistle was blown and the killers obediently got back into their vans, leaving more than 170 dead and others horribly mutilated. There have been no arrests, and no charges have been pressed.

Kuru Karama is half an hour’s drive south of the Nigerian town of Jos, which used to be remembered (in Westminster at least) for a special reason. A young John Major worked as a bank clerk here in the early 1960s before a bad car accident forced him to return to Britain and take up politics. Indeed Bruce Anderson, biographer of the former prime minister, records that ‘the hill country around Jos is one of the more attractive parts of Nigeria. The people and the way of life in no way resembled the chaos, squalor and corruption of Lagos, while the bush, the skies, and the African landscape worked their magic on John Major’.

Today Jos, capital of Plateau State, is the Nigerian epicentre of sectarian violence.

Nigeria’s population of around 170 million people is more or less evenly divided between Christians in the south and Muslims in the north. It is the deadly misfortune of Jos to find itself on the demarcation line. Already this year well over 1,000 people have been killed, and there is no prospect at all of the carnage abating. Director/cameraman Andy Wells and I arrived in the town – advertised in publicity brochures as the ‘home of peace and tourism’ – just after hundreds had been slaughtered during three days of lawless horror. Everywhere we found burnt-out and destroyed homes, cars and shops.

Troops patrolled the streets and there was a strict curfew from 6 p.m. Graffiti warned of future terror: ‘We are coming back very soon’; ‘Get ready 4 a return match’; ‘We are waiting for you in Jesus’ name’ answered by ‘We shall see – Inshallah’. Though open violence had abated, we were told of many ‘silent killings’, with Christians assassinated as they strayed into Muslim areas and vice-versa.

Strangers came forward to show us video footage and photographs taken during what everyone called ‘the crisis’. They were indescribably upsetting: naked, castrated males; the blacked and charred body of a two-day old child; endless skulls hacked open by machetes. Film of Nigerian soldiers hauling a defenceless man out of the back of a van, kicking him and shooting him dead, is being widely circulated.

At the Plateau State Specialist Hospital Dr Golwa Philimon, a surgeon, told us how he hardly slept for three days as he struggled to cope with the casualties. He saved lives to the sound of the machine-gun fire just outside the hospital and with the smell of burning houses in his nostrils. ‘To begin with, ‘ Dr Golwa told us, ‘the casualties had machete wounds or had been hurt by blunt instruments. But after 12 hours this changed and many gunshot wounds came in.’

Dr Golwa said the gunshot wounds had been caused by soldiers wearing ‘fake’ uniforms. Again and again local people told us how they had seen the police and the army resort to indiscriminate killing as they struggled to maintain order – either that or, perhaps more likely, they were simply taking sides.

Both police and army deny any wrongdoing. In all, said Dr Golwa, there were 180 fatalities at his hospital alone. Dr Golwa also told us that casualties were still arriving. He introduced us to Joshua and Danjuma, two Christian villagers who told us they had been ambushed and shot two days earlier in a revenge attack by assailants from the Felani, a nomadic Muslim tribe.

The following day we drove off to their village and found the inhabitants in a state of fear. The tribal chief told us that the Felani attacked every night, that they destroyed crops and looted shops, and that a man had been killed nearby two days earlier. We were told that people were too scared to stay in their own homes, particularly in the nearby village of Dogo, and there was talk that the Felani were amassing for a major attack.

In the backstreets of Jos we met Yahusa Sani, a local gang leader. He was around 30 years old and was missing a right hand, which had been hacked off by a machete when the politician he was guarding came under attack from a rival gang. Yahusa told us how during elections he made good money by stuffing ballot boxes, intimidation and other strongarm tactics. He had been heavily involved in the fighting, so he told us, protecting his own people. ‘We wanted to stop the police coming into our area to stop them shooting us. That is what the police do, ‘ he said.

On the Sunday before we left Jos, we returned to Kuru Karama. I wanted to go to church. Once more we walked through burnt-out buildings till we reached a large church untouched by the mob. Above the altar were deep red drapes, in front of which a large banner pronounced: ‘Serving God With Purpose’. Men sat on the right of the church, gorgeously dressed women on the left. A soldier with a gun lounged at the back, stretching and yawning. The singing was heartbreakingly beautiful. The pastor intoned: ‘We pray for the peace of the nation, we pray for the people of Nigeria.’

He devoted much of his sermon to reading with relish from a long, inflammatory and palpably faked document setting out in great detail Muslim plans to take over and dominate Plateau State. It named leading Muslim generals and politicians as part of an organised conspiracy – Christian Nigeria’s answer to the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. After the service I sat down with the pastor, the Revd Yohanna Musabot. A smallish man, 42 years old, he told me that he had studied at the Theological College of Northern Nigeria and had been a priest for ten years.

I asked him whether he apologised on behalf of the Christian community for the unspeakably evil acts that had been committed just a few yards away from where we were sitting. He refused to do so, saying that there had been crimes on both sides. So I asked him why all the churches in the village were intact. He could not explain. Nor could he name a member of his congregation who had been killed.

I asked him what Jesus would have done. ‘I believe if Jesus was here he would not be happy with what happened, ‘ said the pastor.

I don’t think he was a bad man, the pastor – just caught in a most terrible situation that is way beyond his or anyone’s comprehension. He told me that he had tried to stop the killers but failed. When I checked this out, witnesses told me that he had been more courageous than he claimed – that he had been headbutted and knocked down, and that if he had not run away he would have been lynched.

It came as no surprise at all to learn of an outbreak of fresh horror just a few days after our return to Britain. This time round the principal victims were the Christians, with 200 dead in the village of Dogo alone. Nobody cares.

When Nigeria secured independence from Britain more than half a century ago, it was hailed as a rainbow nation like South Africa or Brazil, embracing many different tribes, sects, religions and ethnic identities. The terrible killings in Jos, and the total in-ability of the state to halt them or even try to punish the perpetrators, raise troubling questions about the future.

Fifty years ago, when a young John Major worked as a bank clerk in Jos, this kind of horror in eastern Nigeria was the background to what turned into the Biafran war, which left a million dead. It’s time to ask how much longer Christian and Muslim tribes can live together in the north, and whether history may be starting to repeat itself, and what we can do to help.

Peter Oborne is associate editor of The Spectator and a columnist for the Daily Mail.

With alarming timeliness, Peter Oborne reports from Nigeria on the sectarian violence between the mainly Muslim north and the Christian south, which has already cost over 1,000 lives this year. But this is not just a religious conflict-it is a battle for land and power with deep roots in ethnic rivalry. He meets the survivors of the violence in the town of Jos and the outlying village of Kuru Karama, where the killing continued for three days. People were shot or hacked to death and their mutilated bodies thrown into wells. In one mass grave, 30 children were dumped in a sewer. The soldiers sent in to restore order embarked on an indiscriminate killing spree. “It is inevitable,” says Oborne at the end of the programme, “that more carnage will follow.” Already he has been proven right.

Is Nigeria’s sectarian violence really down to a Muslim-Christian clash? Journalist Peter Oborne and director Andy Wells say no: instead, this is a deep-rooted struggle for power and land, one which the government is powerless to contain; there are even allegations that the military may be behind some of the outrages. In village after village, we witness the aftermath of the massacres, including bodies thrown down wells and blackened patches where human beings have been burned alive. Civil war looks all too inevitable. AJC

The recent sectarian violence in Nigeria has been put down to clashes between Muslims and Christians. But as this harrowing report suggests, the reality involves a complex battle for land and power. Reporter Peter Oborne and director Andy Wells gained exclusive entry to the town of Jos. After a massacre that left 500 dead, they find violence still erupting despite a military enforced curfew. They also witness the devastation in Kuru Karama where they uncover claims of police involvement.

Anyone who’s been following BBC2’s ‘Blood and Oil’ this week might also be interested in this (as they say on Amazon). Peter Oborne report on the events that led to the recent sectarian violence in Nigeria, uncovering evidence that the conflict is not just about religion, but a battle for land and power with deep roots in ethnic rivalry. And the military, it seems, is busy fuelling the fighting, aided by the government.

This edition is surely more under-reported than unreported, as the recent bloodletting in Nigeria made headlines around the world. Peter Oborne and his director filmed in Jos in the aftermath of an earlier outbreak of sectarian violence there, concentrating on a massacre in a nearby village. Oborne argues that other forces are at work in the tension between Christians and Muslims, such as competition for land and the ambiguous role of Nigeria’s armed forces.